Why the way healthcare professionals measure patient pain might soon be changing

/Why the way healthcare professionals measure patient pain might soon be changing

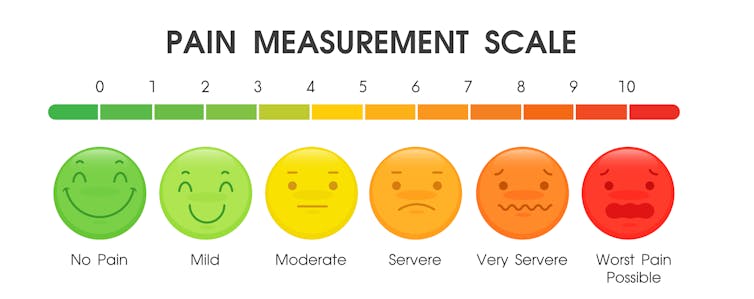

The last time you went to see a doctor, it was probably because you were in pain – it’s by far the main reason people access the health service. And if you did go because of pain, your doctor probably asked you to rate it on a scale from zero to ten. Zero being no pain and ten being the worst pain you can imagine. This pain scale is so simple and intuitive, that it’s hard to imagine a time when doctors didn’t have it.

Before World War II, measuring pain mainly focused on how much a specific stimulation would be needed to elicit a pain response. This is the so-called pain threshold, the point at which an external stimulus changes from a non-painful sensation to a painful one. For example, increasing pressure is applied to the skin until the subject reports feeling pain. Early psychologists also explored pain tolerance, where a painful stimulus would be applied and the duration a person could withstand the pain would be measured. But neither of these measured the nature or intensity of pain.

During and shortly after World War II, pain science became a more recognised topic of study within medicine. Kenneth Keele, a cardiologist, focused more on the need to measure the effectiveness of treatments. Patients were asked to rate their pain relief after a specific treatment on a five-point scale, ranging zero to four, where zero represented no relief and four, complete relief.

But since pain doesn’t always neatly fall into one of five categories, in the 1960s, three psychiatrists – Michael Bond, Issy Pilowsky and Graham Spear – built on Keele’s work and developed the visual analogue scale (VAS), a 10cm horizontal line, which in current practice has the words “no pain” on the left-hand side and “worst pain imaginable” at the right. Patients are instructed to place a mark on the line that best represents their pain at that moment.

The line would be measured in centimetres and recorded. This tool acts like a sliding scale rather than Keele’s five categories. Over the years, the wording for “worst pain imaginable” has changed. It started as “severe pain” and doctors often use different terms. But all these different phrases can influence the patient’s understanding of what their worst pain might be. This scale also has its variants, with a verbal version, the numerical rating scale being a commonly used measure today. There is also a version that uses facial expressions for children or those with communication difficulties.

Measuring the threshold, tolerance and intensity of pain is useful, but these measures don’t address the complex nature of what pain feels like. Alongside this history of pain intensity measurements, there was a comparative approach exploring the feeling of pain.

In 1939, Karl Dallenbach developed a list of 44 pain descriptor words that were divided into five groups to use the patient’s reported feeling to help quantify the sensation. In 1975, Ronald Melzack and colleagues further developed this idea by creating the McGill pain questionnaire, which consists of about 80 words, divided into six sensory categories, which are used to describe the sensation of pain. For example, “shooting”, “aching”, “throbbing”, “dull”, and “tight” together with a ranking of intensity against each word, such as “none”, “mild”, “moderate” and “severe”. People rank the intensity of each of the descriptive “feeling” words. The different categories and different intensity ranking are allocated a score and this a total score can be calculated.

Read more: Five everyday myths that make it hard to understand pain

The idea behind this more complex approach is to combine the descriptive feeling of pain with a numerical weighting of intensity. But one complexity is that the descriptor words may mean something different – or not even exist – in different cultures and languages. Different cultures have different descriptors for pain with some cultures having a smaller range of words used to describe what pain feels like. To help reduce the language conflict of pain descriptors, some papers publish the conversion of the English McGill into other languages to ensure the words and their meanings are comparable.

Pain conversation

Both the visual analogue scale type measures and the pain descriptors type measures may well be evolving into a new generation of pain measurement. It is reported that the VAS is going out of fashion, and there is a trend to evaluate pain with a “pain conversation” rather than a quantifiable measuring tool.

Since pain is unique to each person, integrating how they interpret their own pain and how the pain affects their ability to perform activities is thought to be more relevant to the patient. A pain conversation will involve a series of questions that assess the extent to which day-to-day activities are affected by pain, such as opening a jar or making a meal.

In healthcare, measurements are taken as part of a normal assessment, which helps doctors form a diagnosis, guide treatment options and see if someone is improving. Despite the amazing advances in many areas of medicine, being able to measure the sensory, emotional phenomenon that is pain, which all human beings experience, continues to be a challenge.![]()

Richard Day, Lecturer, Physiotherapy, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.